By Amna Khwaja

When I was a little girl my father would take me my by the hand and walk me across the road from his shop on Young Street, Kensington, so that we could look at the marzipan cats, lined up in rows, on the sweet counter in Barkers department store. The cats had small heads and pointy ears and pot bellies – and I liked the yellow ones the best. But even more than the cats, I liked being with my father. I liked it so much I was his tiny office assistant, scrawling a little girl’s signature on his cheque book, and whisking the handle backwards and forwards on the old credit card machine, wasting endless paper slips. I was the chosen child.

My father was a quiet and reserved man with a dry, self depreciating, sense of humour. He arrived from Pakistan in the 1950s after working in France, Switzerland, Japan and even Iran. Although he came from a distinguished family of doctors, his sensitive nature had undermined a prospective career in medicine. A spell working in an operating theatre led to a collapse, and after that he concentrated on accounts; he was a figures man running a dizzying array of family businesses, including a nanny agency, a book supplier to Holborn Law College, and a famous boutique off Kensington High Street that imported cheesecloth shirts and supplied Mary Quant.

Dressed in his polo neck sweater, hound-tooth blazer and carrying a briefcase, my father was a businessman about town. With his dark hair swept back, and his moustache, he was once called the best-dressed gentleman in Kensington. Some said he looked a little like Omar Sharif. Certainly, my father did not believe in casual attire, and he claimed never to have worn a pair of jeans in his life.

Whatever his business skills, my father was much more than an accountant – he was a dreamer too. As a young man his tastes had included playing the violin, and writing satirical articles for his college magazine. On outings I would sit beside him in the front seat of our Mercedes while we cruised across West London, tuning the radio into classical music. My sister sat in the backseat and wanted to listen to Wham.

First and foremost my father was a family man, although we arrived quite late in his life after a short-lived marriage to my young Catholic Irish mother, whom he had met in the tax office. After they separated, I went everywhere with him; a quiet ghost who accompanied him on all his appointments to the town hall, the boutique, and the bank. At night we watched his favourite viewing – Miss Marple.

No one noticed anything was wrong, until the day, years later, of my university graduation. We met at my Aunty’s house in Fulham, and climbed into the car for the ride across town to the ceremony. As we approached the tunnel near the Barbican my father became confused. He seemed to forget where he was. Who he was. We drove round and round a complicated series of streets – until something clicked and my father was my father once more. We arrived with a little time to spare.

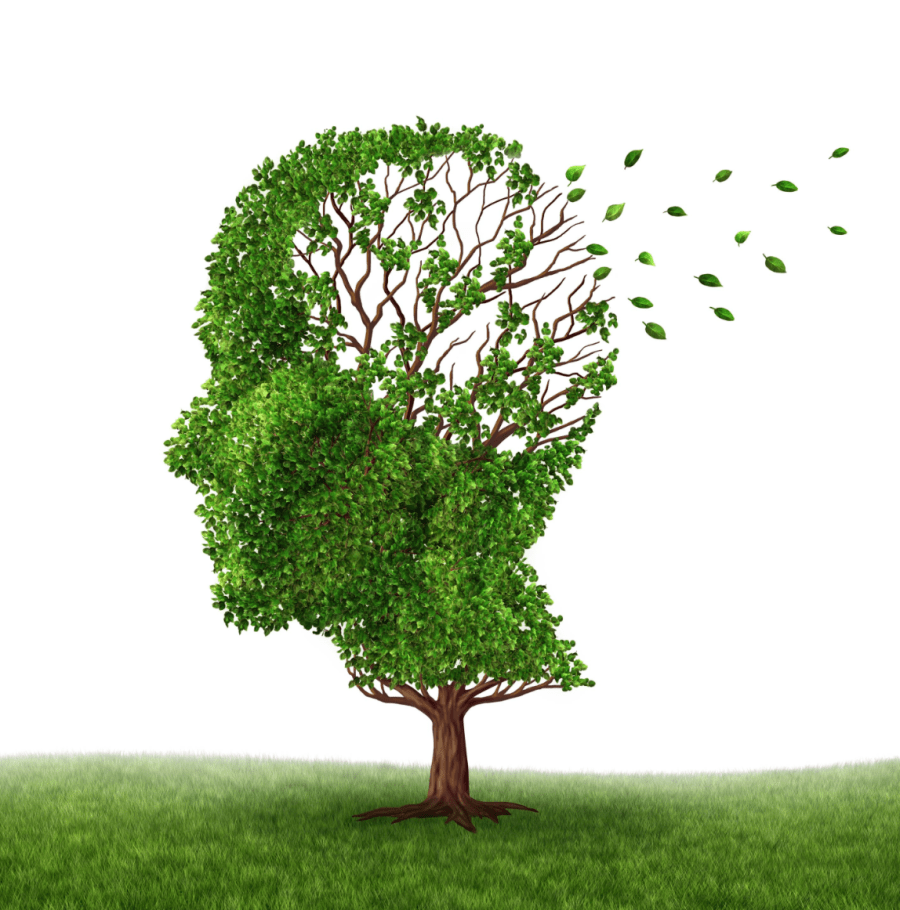

For years we ignored the signs, but of course my father was one of the millions of people diagnosed with frontal lobe Alzheimer’s. For him his disease has been a dizzying, terrifying descent – and for me also. The carers who fondly call him Abdul, but a shock to me who only ever heard him called Mr Khwaja. The handfuls of pens and spoons cluttering his pockets. The care home with its angry and confused residents locked in death’s waiting room. Well meaning people tell me he is ‘happy in his world’, but what I sense from him mostly is frustration.

With the support of our family, especially my auntie and her daughter, we weathered the storm until he needed to be attended to full-time. Until he became a sun-downer, as they are known in the dementia world; his night our day, pacing up and down with those around him unable to rest incase, in a stray second, he opens a door and escapes, like a toddler running into a busy road. With such responsibility comes tremendous guilt, wishing on some level that his torment could be over, but at the same time not wanting him to go.

Alzheimer’s is no longer a hidden disease, it seems to have eaten its way through our world like it eats its way through the brain – affecting more people than ever. We don’t know why.

As my father tells me every time I see him, with a look of nervousness on his face that wants to lead him back to his old life – there’s a lot of work to be done. A lot of work on the origins of the disease, a lot of work on caring. My father doesn’t know where his life’s work lies anymore, he only knows he should be out there doing it.